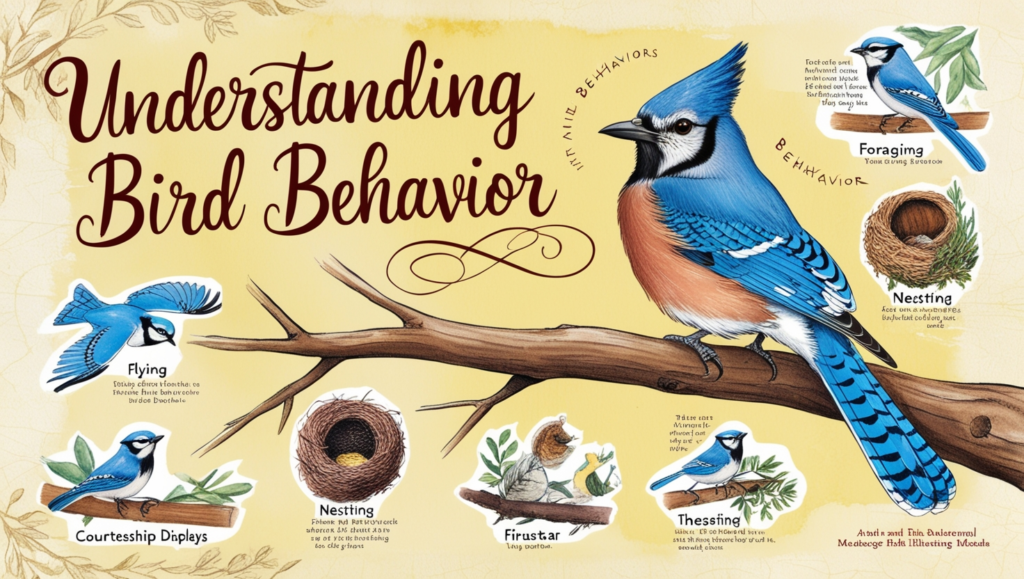

Birds are fascinating creatures with a wide range of behaviors that often leave us curious about their meanings. Whether you’re a seasoned birdwatcher or a casual observer, understanding bird behavior can deepen your appreciation for these feathered friends and enhance your birdwatching experience. In this guide, we’ll explore some common bird behaviors and what they signify.

I. Singing and Calling:

Birds are renowned for their songs and calls, which are among the most distinctive and captivating aspects of their behavior. These vocalizations are not just random noises but are crucial tools for communication, survival, and reproduction. In this article, we will explore the different types of bird songs and calls, their purposes, and what they reveal about the birds making them.

1. Bird Songs: A Melody of Communication

Bird songs are typically longer and more complex than calls, often consisting of a series of repeated notes and phrases. Songs are primarily used by male birds to attract mates and establish territories. Each species has its own unique song, and in some cases, individual birds may have their own variations or “dialects” depending on their region.

- Attracting Mates: During the breeding season, male birds sing to showcase their fitness and attract females. A strong, consistent song indicates a healthy, dominant male, which is attractive to potential mates. For example, the nightingale is famous for its powerful, melodious song, which it uses to woo females during the night.

- Territorial Defense: Songs also serve as a warning to other males, signaling that a territory is already claimed. By singing from prominent perches, a male bird asserts its presence and deters rivals from encroaching on its space. The louder and more persistent the song, the more likely it is to keep competitors at bay.

2. Bird Calls: The Language of Survival

Unlike songs, bird calls are generally shorter and simpler. They are used for a variety of everyday purposes, such as communication between members of a flock, signaling danger, or coordinating movements.

- Alarm Calls: One of the most critical uses of calls is to alert others to danger. These alarm calls are often sharp, high-pitched, and repeated, designed to be heard over long distances and to warn other birds of predators. For instance, a robin’s alarm call can signal the presence of a cat or a hawk, prompting other birds to take cover.

- Contact Calls: Birds use contact calls to stay in touch with each other, especially when foraging or migrating in groups. These calls help maintain group cohesion and ensure that individuals do not get lost. For example, sparrows frequently use soft, chip-like calls to communicate while feeding in flocks.

- Begging Calls: Young birds use begging calls to signal hunger to their parents. These calls are usually high-pitched and insistent, prompting the parents to bring food to the nest. As the chicks grow, these calls can become more complex, sometimes mimicking the adult songs.

3. The Role of Mimicry in Bird Songs and Calls

Some bird species, like the mockingbird and the lyrebird, are known for their ability to mimic the sounds of other birds, animals, and even human-made noises. This mimicry serves several purposes:

- Attracting Mates: In some species, males use mimicry to expand their song repertoire, making them more attractive to females. A diverse range of sounds can indicate a high level of intelligence and adaptability, traits that are desirable in a mate.

- Territorial Defense: Mimicking the calls of predatory birds or other species can also help to deter rivals from entering a bird’s territory. This form of vocal trickery can give the impression that a territory is already crowded or that a predator is nearby.

4. Seasonal Changes in Bird Songs and Calls

Bird songs and calls can vary with the seasons. During the breeding season, songs become more frequent and complex as males compete for mates and territories. In contrast, during the non-breeding season, singing may decrease, and birds may rely more on calls to communicate about food sources or warn of predators.

- Dawn Chorus: One of the most enchanting phenomena in the bird world is the dawn chorus, where numerous bird species sing together at dawn, particularly during the spring. This synchronized singing serves multiple purposes, including reinforcing territory boundaries and attracting mates at the start of the day.

5. How to Identify Birds by Their Songs and Calls

Learning to identify birds by their songs and calls can greatly enhance your birdwatching experience. Start by focusing on the common birds in your area and learning their distinct sounds. There are many apps and online resources available that can help you match sounds to specific species.

Context: Consider the context in which the sound is heard. Is it a territorial song at dawn, an alarm call in the presence of a predator, or a soft contact call during feeding?

Repetition and Rhythm: Notice the pattern of repetition and the rhythm of the song or call. Some birds have fast, repetitive songs, while others may have slow, drawn-out notes.

Pitch and Tone: Pay attention to the pitch and tone. Some birds, like the American robin, have a cheerful, melodic tone, while others, like the black-capped chickadee, have a simpler, more mechanical sound.

II. Preening

Preening is one of the most essential and fascinating behaviors observed in birds. It’s an activity that goes beyond simple grooming—preening plays a vital role in a bird’s overall health, social interactions, and even survival. In this article, we’ll explore what preening is, why it’s so important, and what it can tell us about bird behavior.

1. What Is Preening?

Preening is the act of a bird using its beak to clean, arrange, and maintain its feathers. This behavior is akin to a daily hygiene routine for birds, ensuring that their feathers remain in optimal condition. Birds spend a significant amount of time preening, often several hours a day, as it is crucial for their well-being.

2. The Importance of Preening

Feathers are essential for many aspects of a bird’s life, including flight, insulation, waterproofing, and communication. Preening helps maintain these functions by:

- Cleaning Feathers: Birds use their beaks to remove dirt, dust, parasites, and other debris from their feathers. Keeping feathers clean is vital for proper insulation and the bird’s ability to stay warm in cold conditions.

- Aligning Feathers: During preening, birds carefully realign their feathers. Proper alignment is crucial for efficient flight, as it reduces drag and allows for smoother, more controlled movements. Additionally, well-aligned feathers help maintain the bird’s streamlined shape, which is essential for both flight and swimming in waterfowl.

- Spreading Preen Oil: Birds have a special gland located near the base of their tail called the uropygial or preen gland. This gland secretes an oily substance that birds spread over their feathers during preening. Preen oil helps waterproof the feathers, keeping them flexible and preventing them from becoming brittle. This is particularly important for waterfowl, as it ensures they stay dry and buoyant.

3. Social Aspects of Preening

Preening is not only a solitary activity; it also plays a significant role in social interactions among birds.

- Allopreening: Allopreening is when birds preen each other, usually in areas they cannot easily reach themselves, such as the head and neck. This behavior is common among bonded pairs, such as mates or parents and their offspring, and it helps strengthen social bonds. Allopreening can also reduce tension within a flock, fostering cooperation and social cohesion.

- Courtship and Bonding: In many species, preening is part of courtship rituals. Birds may preen themselves or each other as a way of showing affection and reinforcing pair bonds. This behavior is especially important during the breeding season, as it helps maintain the bond between mates and ensures cooperation in raising offspring.

4. Preening as a Sign of Health

The state of a bird’s feathers can tell us a lot about its health. Healthy birds with well-maintained feathers are likely to be in good condition, while birds with unkempt or damaged feathers may be dealing with stress, illness, or parasites.

- Molting: Birds periodically molt, shedding old feathers and growing new ones. During this time, preening is even more critical as new feathers, or pin feathers, emerge. These new feathers are coated in a protective sheath that birds must remove through preening to allow the feathers to fully expand.

- Stress or Illness: Birds that are sick or stressed may preen less frequently or may over-preen, leading to feather damage. Over-preening or feather-plucking can also be a sign of boredom or anxiety, especially in captive birds. Observing a bird’s preening habits can provide important clues to its overall well-being.

5. Preening and Environmental Adaptation

Preening behavior can vary depending on a bird’s environment and lifestyle.

- Waterproofing in Aquatic Birds: Waterfowl, such as ducks and swans, are particularly reliant on preening to maintain the waterproofing of their feathers. The preen oil they apply during preening creates a barrier that prevents water from soaking into their down feathers, which could lead to hypothermia.

- Dust Bathing: Some birds, like sparrows and pigeons, engage in dust bathing as part of their preening routine. Dust bathing helps remove excess oil and parasites from their feathers, which they then clean off through preening.

- Sunbathing: Birds sometimes use the sun’s warmth to help with preening. By spreading their wings and fluffing their feathers while basking in the sun, they allow sunlight to penetrate through their feathers, which can help eliminate parasites and make preening more effective.

III. Feeding Behavior

Feeding behavior is one of the most varied and fascinating aspects of bird behavior. Birds have evolved a wide range of strategies and techniques to find, capture, and consume food. These behaviors are not only essential for their survival but also provide insights into their ecology, diet preferences, and even social structures. In this article, we’ll explore the different feeding behaviors exhibited by birds and what they reveal about these remarkable creatures.

1. Foraging Techniques

Birds use various foraging techniques depending on their species, habitat, and the type of food they seek. These techniques are often specialized and reflect the bird’s adaptations to its environment.

- Probing and Picking: Many birds, such as woodpeckers and shorebirds, use their beaks to probe into bark, soil, or sand to find insects, worms, or other invertebrates. For example, woodpeckers have strong, pointed beaks that allow them to drill into tree bark to extract insects. Shorebirds, like sandpipers, have long, slender beaks ideal for probing into wet sand for hidden prey.

- Hawking: Some birds, like flycatchers and swallows, catch their prey mid-flight. This behavior, known as hawking, involves agile flight patterns and quick reflexes to snatch insects out of the air. Swallows, for instance, are expert aerial hunters, capturing insects in mid-flight with incredible precision.

- Gleaning: Gleaning involves picking food off surfaces, such as leaves, branches, or the ground. Warblers and chickadees are well-known gleaners, moving quickly through foliage to pick off insects, spiders, and other small prey.

2. Seed and Nut Feeding

Birds that feed on seeds and nuts have developed specific behaviors and physical adaptations to help them access these food sources.

- Cracking Seeds: Birds like finches, sparrows, and grosbeaks have strong, conical beaks designed for cracking open seeds. These birds often use their beaks to crush seeds and extract the nutritious kernels inside. For example, the American goldfinch uses its sharp beak to slice through the tough outer shell of sunflower seeds.

- Caching: Some birds, such as jays and nuthatches, store food for later consumption. This behavior, known as caching, involves hiding seeds or nuts in various locations, such as in tree bark or buried in the ground. Birds with this behavior have excellent spatial memory, allowing them to return to these caches when food is scarce.

3. Carnivorous Feeding

Birds of prey, or raptors, exhibit specialized feeding behaviors tailored to their carnivorous diets. These birds are adapted to hunt, capture, and consume other animals, ranging from insects to mammals.

- Hunting Techniques: Raptors, like eagles, hawks, and owls, use a combination of keen eyesight, sharp talons, and powerful beaks to capture and kill their prey. For example, a hawk might soar high above an open field, scanning for small mammals before diving at high speed to seize its target with its talons.

- Scavenging: Some birds, like vultures, feed on carrion (dead animals). Scavenging is a crucial ecological role, as it helps to clean up dead animals and recycle nutrients back into the ecosystem. Vultures have strong stomach acids that allow them to safely consume decaying meat that would be harmful to other animals.

4. Nectar Feeding

Nectar-feeding birds, such as hummingbirds and sunbirds, have evolved specialized behaviors and physical adaptations to extract nectar from flowers.

- Hovering: Hummingbirds are the most well-known nectar feeders, using their ability to hover in place while they sip nectar from flowers. Their long, slender beaks and specialized tongues allow them to reach deep into flowers to access the sugary liquid. This behavior not only feeds the bird but also plays a role in pollination, as the bird transfers pollen from one flower to another.

- Flower Preferences: Nectar-feeding birds are often attracted to brightly colored flowers, particularly red and orange, which signal a rich nectar source. These birds have excellent memory and can remember which flowers they’ve already visited and when those flowers will replenish their nectar supply.

5. Opportunistic Feeding

Some birds are opportunistic feeders, meaning they adapt their diet and feeding behavior based on what food is available. These birds are highly adaptable and can thrive in a variety of environments.

- Omnivorous Diets: Birds like crows, gulls, and pigeons have omnivorous diets, consuming a wide range of food items, including fruits, seeds, insects, and even human scraps. Their opportunistic nature allows them to exploit a variety of food sources, making them successful in both urban and wild environments.

- Tool Use: Certain birds, such as crows and woodpecker finches, are known for using tools to help them access food. For instance, crows have been observed using sticks to extract insects from tree bark, demonstrating their intelligence and problem-solving abilities.

6. Social Feeding Behavior

Feeding behavior can also be influenced by social structures and interactions within bird species.

Cooperative Feeding: In some species, birds work together to obtain food. For instance, Harris’s hawks are known for their cooperative hunting strategies, where several birds work together to flush out prey and capture it. This behavior enhances their hunting success and allows them to tackle larger prey than they could on their own.

Flocking: Some birds feed in flocks, which can provide safety in numbers and increase foraging efficiency. For example, starlings often feed in large flocks, moving together in synchrony as they search for food. Flocking can help reduce the risk of predation, as predators are less likely to attack a large group.

IV. Courtship Displays

Courtship displays are among the most visually and behaviorally fascinating aspects of bird behavior. These elaborate rituals, ranging from intricate dances to vibrant plumage displays, are essential for attracting mates and ensuring the continuation of the species. In this article, we will delve into the purpose of courtship displays, the various forms they take, and what they reveal about the birds performing them.

1. The Purpose of Courtship Displays

Courtship displays serve several critical functions in the bird world. Primarily, they are a means for birds to attract mates by demonstrating their fitness, genetic quality, and suitability as a partner. These displays can also help to establish and reinforce pair bonds, ensuring cooperation in raising offspring.

- Attracting a Mate: The primary goal of courtship displays is to attract a mate. Males often take the lead in these displays, showcasing their physical attributes, strength, and vitality. Females observe these displays and choose a mate based on the quality of the performance, which signals the male’s genetic fitness.

- Establishing Territory: In some species, courtship displays also serve to establish or defend a territory. Males may display to warn off rivals while simultaneously attracting a mate, ensuring that the chosen territory is suitable for raising young.

- Reinforcing Pair Bonds: For species that form long-term pair bonds, courtship displays help to maintain and strengthen these relationships. These displays can be a form of communication that reaffirms the pair’s commitment to each other, especially during the breeding season.

2. Types of Courtship Displays

Birds have evolved a wide variety of courtship displays, each unique to their species and environment. These displays can be visual, auditory, or a combination of both, and they often involve elaborate rituals that are as captivating as they are complex.

- Visual Displays: Many birds rely on visual displays, using their colorful plumage, dramatic postures, or impressive structures to attract mates.

- Plumage Displays: Peacocks are perhaps the most famous example of a bird using its plumage in courtship. The male peacock fans out its long, iridescent tail feathers, creating a dazzling display of eyespots that attract females. The size, color, and symmetry of the eyespots are all factors that females consider when selecting a mate.

- Dance Displays: Some birds perform intricate dances as part of their courtship rituals. The male bird-of-paradise, for example, performs a complex dance that includes a series of hops, flips, and wing movements, all designed to showcase his vibrant plumage and agility. These dances are often accompanied by vocalizations or other sounds, adding to the overall display.

- Building Structures: Male bowerbirds are known for constructing elaborate structures, called bowers, to impress females. These bowers are often decorated with colorful objects, such as flowers, berries, and even bits of plastic. The male’s ability to build and decorate the bower is a key factor in attracting a mate, as it signals his creativity and resourcefulness.

- Auditory Displays: Sound plays a significant role in courtship for many bird species. Birds use songs, calls, and even mechanical sounds to communicate with potential mates.

- Songs: Male songbirds are known for their melodic and complex songs, which they use to attract females and establish territory. Each species has its own unique song, and individual males may develop their own variations or “dialects.” A strong, clear song is often a sign of a healthy, dominant male.

- Mechanical Sounds: Some birds produce sounds not with their voices but through specialized physical movements. The club-winged manakin, for example, creates a high-pitched sound by rapidly rubbing its wings together. This mechanical sound is part of an elaborate courtship display that also includes acrobatic movements and vocalizations.

3. Role of Sexual Selection in Courtship Displays

Courtship displays are a key component of sexual selection, a process in which certain traits become more common in a population because they increase an individual’s chances of mating and passing on their genes.

- Mate Choice: In many bird species, females choose their mates based on the quality of the male’s courtship display. This choice drives the evolution of more elaborate and showy displays over time, as males with the most impressive displays are more likely to reproduce.

- Competition: Males often compete with each other for the attention of females, leading to the evolution of traits that enhance their competitive edge. These traits might include brighter plumage, more complex songs, or larger physical size.

- Costly Signals: Courtship displays can be costly in terms of energy expenditure and increased visibility to predators. However, these costly signals are also a reliable indicator of a male’s fitness. A male that can afford to engage in such displays is likely to be in good health and possess strong genes, making him an attractive mate.

4. Courtship Displays and Species Recognition

Courtship displays also play a crucial role in species recognition, ensuring that birds mate with individuals of their own species. This is especially important in areas where multiple closely related species coexist.

- Species-Specific Displays: Each bird species has its own unique courtship display, which helps to prevent hybridization between species. For example, different species of warblers may have similar songs, but their courtship dances or plumage patterns are distinct, allowing females to choose the correct mate.

- Isolation Mechanisms: These species-specific displays act as isolation mechanisms, maintaining the integrity of species by reducing the likelihood of interbreeding. This ensures that the offspring produced are well-suited to their particular environment.

5. Human Impact on Courtship Displays

Human activities, such as habitat destruction, pollution, and climate change, can affect the ability of birds to perform their courtship displays and, consequently, their ability to reproduce.

- Habitat Loss: Many courtship displays require specific habitats, such as open fields, dense forests, or wetlands. Habitat loss due to deforestation, urbanization, or agriculture can reduce the availability of these essential display sites, making it harder for birds to find mates.

- Pollution: Noise pollution can interfere with auditory displays, making it difficult for birds to hear and respond to each other’s songs. Light pollution can also disrupt the timing of displays, particularly for species that rely on dawn or dusk periods for their courtship rituals.

- Climate Change: Changes in climate can alter the timing of breeding seasons, potentially causing a mismatch between the availability of food and the needs of breeding birds. This can impact the success of courtship displays and the subsequent raising of young.

V. Migration Patterns

Migration is one of the most remarkable and awe-inspiring behaviors observed in birds. Each year, millions of birds travel vast distances across continents, often facing incredible challenges, to find the best habitats for breeding, feeding, and raising their young. This article explores the fascinating world of bird migration, examining why birds migrate, the different patterns of migration, and how they navigate these incredible journeys.

1. Why Do Birds Migrate?

Migration is primarily driven by the need to access resources that are seasonally available in different parts of the world. Birds migrate to take advantage of optimal breeding conditions, food availability, and suitable climates.

- Breeding: Many bird species migrate to specific breeding grounds where the conditions are ideal for raising their young. These areas often have abundant food, fewer predators, and suitable nesting sites. For example, Arctic terns migrate from the Arctic to the Antarctic and back each year to take advantage of the long summer days and abundant food supply at both poles.

- Food Availability: Seasonal changes can significantly impact the availability of food. In colder regions, food sources such as insects, fruits, and nectar become scarce during the winter. To survive, birds migrate to warmer areas where food is more plentiful. For instance, hummingbirds migrate from North America to Central and South America to access the nectar-rich flowers that bloom year-round in tropical regions.

- Climate: Birds also migrate to avoid extreme weather conditions. For example, many species that breed in the temperate zones of North America migrate south to escape the harsh winter conditions and return north when spring arrives.

2. Types of Migration

Birds exhibit a variety of migration patterns, each adapted to the specific needs and conditions of the species. These patterns include long-distance, short-distance, altitudinal, and partial migration.

- Long-Distance Migration: Some birds undertake epic journeys spanning thousands of miles. These long-distance migrants often travel between continents, crossing oceans and deserts to reach their destinations. An example is the bar-tailed godwit, which holds the record for the longest nonstop flight of any bird, covering over 7,000 miles from Alaska to New Zealand.

- Short-Distance Migration: Other birds migrate over shorter distances, often within the same continent. These migrations might be just a few hundred miles, moving between breeding and wintering grounds within the same country or region. American robins, for example, may migrate only a few hundred miles south to escape cold winters.

- Altitudinal Migration: Some birds migrate vertically rather than horizontally, moving up and down mountainsides in response to seasonal changes. This altitudinal migration allows them to find suitable climates and food sources at different elevations throughout the year. For instance, the Himalayan monal migrates to lower altitudes during the winter to avoid snow-covered habitats.

- Partial Migration: In some species, only a portion of the population migrates, while the rest remain in the same area year-round. This is known as partial migration. Factors such as age, sex, and individual health can determine whether a bird migrates or stays. For example, some populations of European blackbirds migrate, while others do not, depending on the availability of food.

3. How Birds Navigate

One of the most astonishing aspects of bird migration is their ability to navigate across vast distances with remarkable precision. Birds use a combination of natural cues, including the sun, stars, magnetic fields, and landmarks, to find their way.

- Sun and Stars: Many birds use the position of the sun during the day and the stars at night to navigate. This celestial navigation requires an internal clock that helps them adjust for the movement of the sun and stars across the sky. For example, indigo buntings are known to use the stars for orientation during their nocturnal migrations.

- Magnetic Fields: Birds have a remarkable ability to detect the Earth’s magnetic field, which they use as a compass to guide their migration. This sense, known as magnetoreception, allows birds to determine their position and direction relative to the Earth’s magnetic poles. Researchers believe that birds may have specialized cells in their eyes or beaks that help them sense magnetic fields.

- Landmarks: Birds also use visual landmarks such as coastlines, rivers, and mountain ranges to navigate. These familiar features help them stay on course and find their way to their destinations. Homing pigeons, for example, are known for their ability to navigate using visual landmarks over long distances.

- Olfactory Cues: Some bird species, particularly seabirds like albatrosses, use their sense of smell to navigate. They can detect specific scents associated with their breeding or feeding grounds, helping them find their way across vast oceans.

4. Challenges of Migration

Migration is an arduous and dangerous journey, fraught with challenges that birds must overcome to survive.

- Predation: Migrating birds are vulnerable to predators, especially during stopovers when they rest and refuel. Raptors such as hawks and falcons often target exhausted migrants, taking advantage of their weakened state.

- Habitat Loss: The destruction of key stopover sites and wintering grounds due to deforestation, agriculture, and urbanization poses a significant threat to migratory birds. Without these crucial habitats, birds may struggle to find the food and rest they need to complete their migration.

- Weather: Adverse weather conditions, such as storms, strong winds, and extreme temperatures, can be life-threatening for migrating birds. Unexpected weather events can blow birds off course, deplete their energy reserves, or even result in mortality.

- Human-made Obstacles: Human activities have introduced new obstacles for migrating birds, including tall buildings, wind turbines, and power lines. These structures can cause fatal collisions, particularly for birds that migrate at night.

5. Conservation and the Future of Migration

The survival of migratory birds depends on the conservation of their habitats and the protection of the migration routes they rely on. Conservation efforts focus on safeguarding critical breeding, stopover, and wintering sites, as well as addressing the broader environmental threats that impact migration.

- Protected Areas: Establishing protected areas along migration routes is essential for providing safe havens where birds can rest and refuel. These areas need to be managed to ensure they offer the necessary resources, such as food and shelter.

- International Cooperation: Since many migratory birds cross international borders, their conservation requires global cooperation. International agreements, such as the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS) and the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, play a vital role in protecting these species and their habitats.

- Research and Monitoring: Ongoing research and monitoring are crucial for understanding migration patterns and identifying threats. Advances in tracking technology, such as GPS tagging, allow scientists to study migration in greater detail, helping to inform conservation strategies.

- Climate Change: Climate change poses a significant challenge to migratory birds, altering the timing of migration, shifting habitats, and disrupting food availability. Conservation efforts must also address the impacts of climate change to ensure the long-term survival of migratory species.

VI. Nesting and Parenting

Nesting and parenting are among the most critical aspects of bird behavior, ensuring the survival of the next generation. From selecting the perfect nesting site to caring for their young, birds exhibit a wide range of strategies to raise their offspring successfully. In this article, we will explore the fascinating behaviors associated with nesting and parenting, examining how different species approach these essential tasks.

1. Nest Building: A Safe Haven for the Next Generation

The process of nest building is crucial for the protection and development of bird eggs and chicks. The type of nest a bird builds depends on its species, habitat, and the threats it faces.

- Types of Nests: Birds build a variety of nests, each suited to their specific needs. Some common types include:

- Cup Nests: These are perhaps the most recognizable nests, typically built by songbirds such as robins and sparrows. Cup nests are usually made from twigs, grasses, and other plant materials, and are often lined with softer materials like feathers or fur for insulation.

- Cavity Nests: Many birds, such as woodpeckers and some owls, prefer to nest in cavities, either in tree trunks or artificial structures like nest boxes. These nests offer protection from predators and the elements.

- Ground Nests: Some birds, such as shorebirds and ground-nesting birds like killdeer, create simple scrapes in the ground to lay their eggs. These nests rely on camouflage to protect the eggs from predators.

- Platform Nests: Larger birds like eagles and ospreys build platform nests, which are often large and sturdy, made from sticks and other durable materials. These nests are typically located in high, inaccessible places, providing safety from ground predators.

- Weaver Nests: Some species, like the weaver birds, construct elaborate nests by weaving grasses and other plant fibers into intricate structures. These nests are often communal, with many birds building their nests in close proximity.

- Nesting Sites: Birds choose nesting sites based on several factors, including the availability of food, safety from predators, and proximity to water. Some birds are highly selective, returning to the same site year after year, while others may build new nests each breeding season.

- Nest Construction: The construction of a nest is a labor-intensive process that requires both skill and instinct. Birds gather materials from their environment, often making multiple trips to collect the necessary components. The male and female may work together, or in some species, one parent (usually the female) takes on the primary responsibility.

2. Egg Laying and Incubation: The Beginning of New Life

Once the nest is complete, the next stage in the reproductive process is egg laying and incubation. The number of eggs, known as a clutch, varies greatly among species, as does the method of incubation.

- Egg Laying: The timing of egg laying is crucial and is often synchronized with the availability of food and optimal weather conditions. Some birds lay a single egg, while others may lay several, depending on their reproductive strategy. The eggs are usually laid at intervals, and the process can take several days.

- Incubation: After the eggs are laid, they must be kept warm for the embryos to develop. Incubation is typically carried out by one or both parents, depending on the species. Birds with both parents involved in incubation often take turns, allowing one to forage while the other stays with the eggs.

- Brood Patches: During incubation, many birds develop a brood patch, a featherless area on their abdomen that allows for direct contact with the eggs, ensuring efficient heat transfer.

- Incubation Period: The incubation period, the time it takes for the eggs to hatch, varies by species. Smaller birds may have incubation periods as short as 10-14 days, while larger birds, such as albatrosses, may incubate their eggs for up to 80 days.

- Protective Behavior: While incubating, birds are highly vigilant, protecting their nests from predators and environmental threats. Some birds use camouflage, while others may aggressively defend their nests from intruders.

3. Hatching and Chick Rearing: The Demands of Parenthood

Once the eggs hatch, the real work of parenting begins. The care of chicks is a demanding task, requiring constant attention, feeding, and protection.

- Hatching: Chicks typically hatch after a period of incubation, using a specialized egg tooth to break through the eggshell. The hatching process can take several hours or even days, depending on the species and the condition of the chick.

- Altricial vs. Precocial Chicks: Bird species can be divided into two categories based on the condition of their chicks at hatching:

- Altricial Chicks: These chicks are born blind, naked, and helpless, requiring significant parental care. Species like songbirds and raptors fall into this category. Parents must provide warmth, protection, and frequent feeding until the chicks are strong enough to leave the nest.

- Precocial Chicks: In contrast, precocial chicks are born with their eyes open, covered in down, and able to move around shortly after hatching. These chicks, such as those of ducks and shorebirds, are often able to feed themselves soon after birth, although they still rely on their parents for protection and guidance.

- Feeding the Young: Feeding is one of the most demanding aspects of parenting. Altricial chicks require frequent feeding, with some species feeding their young up to several times an hour. Parents forage for food and often bring it back to the nest in their beaks or crops. The type of food provided depends on the species, ranging from insects and small mammals to regurgitated food.

- Begging Behavior: Chicks typically beg for food by making loud calls and opening their mouths wide, signaling to their parents that they are hungry. In some species, the chick with the loudest call or the most vibrant mouth coloration may receive more food, ensuring the strongest individuals survive.

- Shared Parenting: In many species, both parents share the responsibility of feeding the young. In others, the female may take on the primary role of feeding while the male provides protection or additional food resources.

4. Fledging: The First Flight

Fledging is a critical milestone in a young bird’s life. This is when the chicks leave the nest and take their first flight.

- Learning to Fly: Fledglings must learn to fly, a process that involves developing muscle strength, coordination, and the confidence to leave the safety of the nest. Parents may encourage their chicks to fledge by withholding food or coaxing them with calls.

- Parental Support: Even after fledging, young birds often continue to receive parental care and guidance. The parents may continue to feed their fledglings while teaching them essential survival skills, such as how to find food and avoid predators.

- Survival Challenges: The fledging period is one of the most dangerous times in a bird’s life. Fledglings are vulnerable to predators, accidents, and harsh environmental conditions. However, successful fledging is critical for the continuation of the species.

5. Extended Care and Family Dynamics

In some bird species, parenting extends beyond fledging, with parents and offspring maintaining close bonds for months or even years.

- Extended Care: Some birds, like swans and cranes, care for their young long after they have fledged, teaching them migration routes and other essential behaviors. These extended family units often work together to protect and support each other.

- Sibling Dynamics: The dynamics between siblings can vary. In some species, older siblings may help care for younger chicks, a behavior known as cooperative breeding. In other cases, sibling rivalry can be intense, with stronger chicks competing for food and resources, sometimes leading to the death of weaker siblings.

6. Human Impact on Nesting and Parenting

Human activities can have significant impacts on the nesting and parenting behaviors of birds.

- Habitat Destruction: Deforestation, urbanization, and agriculture can lead to the loss of critical nesting sites. Birds that rely on specific habitats for nesting may struggle to find suitable sites, leading to reduced reproductive success.

- Climate Change: Changes in climate can affect the timing of breeding seasons, the availability of food, and the suitability of nesting sites. Birds may face challenges in synchronizing their nesting and parenting behaviors with the changing environment.

- Disturbance: Human activities, such as recreational activities near nesting sites, can disturb breeding birds, leading to nest abandonment or reduced care for chicks.

7. Territorial Behavior

Territorial behavior is a crucial aspect of avian life, influencing how birds interact with each other and their environment. This behavior, which involves the defense of a specific area against intruders, plays a key role in securing resources such as food, nesting sites, and mates. In this article, we will explore the various aspects of territorial behavior, including its purpose, the methods birds use to establish and defend their territories, and the impact of territoriality on bird behavior and ecology.

1. Purpose of Territorial Behavior

Territorial behavior is driven by the need to secure and protect resources essential for survival and reproduction. By establishing a territory, birds can ensure access to:

- Breeding Sites: Territories provide a safe and suitable environment for nesting and raising offspring. By defending a territory, birds can prevent other individuals from encroaching on their breeding grounds, reducing competition and increasing the likelihood of successful reproduction.

- Food Resources: Access to food is critical for a bird’s survival and reproductive success. Territorial birds often defend areas that have abundant food sources, such as insect-rich patches or fruit-bearing trees. By maintaining exclusive access to these resources, they can ensure a steady supply of nutrition.

- Shelter and Safety: Territories can offer protection from predators and harsh weather conditions. By controlling an area, birds can select the best sites for shelter and reduce the risk of predation.

2. Methods of Establishing Territories

Birds use various methods to establish and mark their territories, employing both vocal and physical signals to communicate their presence and deter intruders.

- Vocalizations: One of the most common ways birds establish and defend their territories is through vocalizations. Songs and calls serve as both a declaration of ownership and a warning to potential intruders.

- Song: Many bird species use complex and melodious songs to announce their presence and attract mates. For example, the northern cardinal’s song serves as a territorial marker and helps to define the boundaries of its territory. The intensity and variety of the song can signal the bird’s fitness and deter rivals.

- Calls: In addition to songs, birds use various calls to communicate with other individuals. Alarm calls, distress calls, and contact calls can all play a role in territory defense, alerting other birds to the presence of a territorial owner.

- Visual Displays: Birds also use visual displays to mark and defend their territories. These displays can include:

- Posturing: Birds may engage in specific postures or movements to signal their dominance and deter rivals. For example, a male blue jay may puff out its feathers and spread its tail to appear larger and more intimidating.

- Feather Displays: Some species use feather displays to enhance their appearance and assert their dominance. The peacock’s fanned tail feathers, for instance, are not only used to attract mates but also to establish territory by showcasing the bird’s strength and vitality.

- Physical Marking: Certain birds use physical marking to delineate their territory. They may deposit scent markers or engage in behaviors such as defecating in specific areas to leave a visual or olfactory sign of their presence.

- Scent Markers: While less common in birds compared to mammals, some species may use scent markings to define their territory. For example, the European starling has specialized glands that produce a scent used in territorial displays.

- Scratching and Burying: In some cases, birds may scratch the ground or bury objects in specific areas as a way to mark their territory. This behavior can signal to other birds that the area is occupied and defended.

3. Territorial Defense

Once a territory is established, birds must actively defend it from intruders to maintain access to its resources. The methods of defense can vary depending on the species and the level of threat.

- Aggressive Behavior: Territorial defense often involves aggressive behaviors, such as chasing, pecking, or physical confrontations. These actions are intended to drive away rival birds and protect the territory from being encroached upon.

- Chasing: Birds may engage in aerial chases or ground-based pursuits to drive intruders away from their territory. This behavior is common among species that have overlapping territories or frequent interactions with neighboring individuals.

- Physical Confrontations: In some cases, territorial disputes can escalate to physical confrontations, where birds use their beaks, talons, or claws to fight off rivals. Such confrontations are usually limited to short bursts of aggression and often end with one bird retreating.

- Displays of Strength: To avoid physical conflict, some birds use displays of strength to intimidate potential intruders. These displays can include vocalizations, visual displays, or exaggerated movements that signal the bird’s dominance and readiness to defend its territory.

- Boundary Maintenance: Territorial birds regularly patrol the boundaries of their territory to ensure that no intruders are encroaching. This patrol behavior helps to reinforce the territorial boundaries and deter any potential threats.

4. Impact of Territorial Behavior

Territorial behavior has several ecological and social implications for bird populations.

- Population Density: Territorial behavior can influence the density of bird populations in an area. In environments with abundant resources, territories may be smaller and more densely packed. In contrast, in areas with limited resources, territories may be larger and more widely spaced.

- Resource Allocation: Territorial behavior affects how resources are allocated within a habitat. By defending territories, birds can ensure that resources are concentrated in specific areas, which can impact the distribution of food, nesting sites, and other essential resources.

- Breeding Success: The success of breeding can be closely linked to territorial behavior. Birds that maintain well-defined territories with ample resources are more likely to have higher reproductive success. Conversely, birds that face challenges in establishing or defending territories may experience lower reproductive rates.

- Species Interactions: Territorial behavior can influence interactions between different bird species. In areas with high species diversity, territorial disputes and competition can shape the structure of the bird community, affecting species composition and distribution.

5. Human Impact on Territorial Behavior

Human activities can have significant effects on bird territorial behavior and the ecosystems in which they live.

- Habitat Fragmentation: The fragmentation of natural habitats due to urbanization, agriculture, and infrastructure development can disrupt territorial behavior. Birds may struggle to establish and defend territories in fragmented landscapes, leading to increased competition and decreased reproductive success.

- Noise Pollution: Noise pollution from human activities can interfere with birds’ vocalizations and territorial signals. In noisy environments, birds may have difficulty communicating and defending their territories, potentially impacting their breeding success and overall health.

- Habitat Restoration: Conservation efforts focused on habitat restoration and the creation of protected areas can help mitigate the impacts of human activities on territorial behavior. By providing suitable nesting sites and food resources, these efforts support the establishment and maintenance of healthy bird populations.

8. Flocking and Social Behavior

Flocking and social behavior are central to the lives of many bird species, influencing how they find food, migrate, and interact with each other. These behaviors reflect complex social structures and can offer insights into the ecological dynamics of bird communities. This article explores the fascinating world of flocking and social behavior in birds, examining why birds flock, the advantages of social living, and how these behaviors manifest in different species.

1. The Phenomenon of Flocking

Flocking refers to the behavior of birds gathering in groups, often for specific purposes such as foraging, migration, or protection. This behavior can be observed across a wide range of bird species and varies in complexity and scale.

- Types of Flocks: Birds can form different types of flocks based on their social structure and the context in which they gather.

- Feeding Flocks: Many bird species form flocks to search for food. Feeding flocks can be composed of individuals of the same species or mixed-species groups. For example, chickadees and titmice often join together in mixed-species flocks to forage for insects and seeds more efficiently.

- Migratory Flocks: During migration, birds often travel in large, coordinated flocks. These migratory flocks help birds conserve energy, navigate long distances, and reduce the risk of predation. The V-shaped formation of migrating geese is a classic example of how flocking aids in energy conservation and navigation.

- Roosting Flocks: At night, some birds gather in large roosting flocks for safety and warmth. Roosting flocks can provide protection from predators and help birds stay warm during colder months. For instance, starlings form massive roosts that can number in the thousands, creating impressive aerial displays known as murmurations.

2. Benefits of Flocking

Flocking offers several advantages to birds, enhancing their survival and overall fitness. These benefits can be broadly categorized into foraging efficiency, predator protection, and social learning.

- Foraging Efficiency: Flocking can improve foraging efficiency by allowing birds to cover a larger area and locate food sources more effectively. In a feeding flock, individuals can share information about food availability and coordinate their search efforts. This collective foraging behavior can lead to increased food intake and reduced foraging time.

- Information Transfer: Within a flock, birds can learn from each other, picking up on cues and behaviors that lead to food discovery. For example, if one bird finds a rich food source, others in the flock may follow its lead, leading to more efficient foraging for the entire group.

- Predator Protection: Flocking provides safety in numbers, reducing the likelihood of individual predation. By moving in large groups, birds can confuse predators and make it more difficult for them to target a single individual. This collective defense mechanism is particularly effective in reducing the risk of attacks from aerial predators, such as hawks and eagles.

- Dilution Effect: The dilution effect refers to the reduced probability of any single bird being attacked by a predator when in a large group. By spreading out the risk among many individuals, each bird’s chance of being targeted decreases.

- Confusion Effect: The confusion effect occurs when a predator is overwhelmed by the sheer number of moving targets. This visual disorientation makes it difficult for the predator to focus on and capture a specific bird.

- Social Learning: Social learning is another benefit of flocking, allowing birds to acquire new skills and behaviors from their peers. Young birds and new flock members can observe and mimic the actions of experienced individuals, learning important survival skills such as foraging techniques and predator avoidance strategies.

3. Social Structures and Hierarchies

Within flocks, birds often establish complex social structures and hierarchies that influence their interactions and behaviors. These social dynamics can vary widely among species and can impact how individuals relate to each other within the group.

- Dominance Hierarchies: Many bird species exhibit dominance hierarchies within their flocks. These hierarchies determine access to resources, such as food and nesting sites, and can influence social interactions. Dominant individuals may have priority access to resources, while subordinate birds may need to defer to those higher in the hierarchy.

- Aggression and Submission: Dominance hierarchies are often maintained through displays of aggression and submission. Dominant birds may assert their status through vocalizations, physical posturing, or aggressive behavior, while subordinate individuals may show submissive behaviors to avoid conflict.

- Coalitions and Alliances: Some bird species form coalitions or alliances within flocks. These social bonds can facilitate cooperation and mutual support among group members. For example, in some corvid species, individuals form alliances to help each other in foraging or defense.

- Cooperative Breeding: In species with cooperative breeding, such as the purple martin, non-breeding individuals within a flock may assist in raising the young of breeding pairs. These cooperative behaviors enhance the survival of the offspring and strengthen social bonds within the group.

- Fission-Fusion Dynamics: In some species, flocks exhibit fission-fusion dynamics, where the size and composition of the group change frequently. This flexibility allows birds to adapt to varying environmental conditions and social needs. For example, elephants and some primates display similar fission-fusion dynamics in their social groups.

4. Flocking Behavior in Different Species

Different bird species exhibit a range of flocking behaviors, each adapted to their ecological niches and social structures.

- Passerines (Songbirds): Many passerines, such as sparrows and warblers, form flocks primarily for foraging and protection. These flocks can be highly dynamic, with individuals constantly moving and interacting as they search for food and avoid predators.

- Waterfowl: Waterfowl, including ducks and geese, often form large, organized flocks during migration. Their V-shaped formations help them conserve energy and navigate long distances. During the breeding season, these flocks may break into smaller groups as individuals establish territories.

- Seabirds: Seabirds, such as gulls and pelicans, often form large, mixed-species flocks at sea. These flocks can provide opportunities for cooperative feeding and protection from predators. Seabirds may also engage in synchronized diving and foraging, enhancing their efficiency in locating prey.

- Raptors: While most raptors are solitary hunters, some species, such as hawks and eagles, may form temporary flocks during migration or in areas with abundant food. These gatherings can facilitate social interactions and aid in locating prey.

5. Human Impact on Flocking and Social Behavior

Human activities can influence flocking and social behavior in birds, often with both positive and negative effects.

Conservation Efforts: Conservation efforts that focus on preserving and restoring habitats can support healthy flocking behavior by maintaining the resources and conditions that birds need to form and sustain flocks. Creating and maintaining protected areas and wildlife corridors can help mitigate the effects of habitat loss.

Habitat Destruction: The destruction of natural habitats can disrupt flocking behavior by reducing the availability of food sources and suitable roosting sites. Birds may struggle to form and maintain flocks in fragmented or degraded environments.

Urbanization: Urban areas can provide new opportunities for flocking, such as in city parks or artificial roosting sites. However, urban environments also introduce challenges, including increased noise and pollution, which can impact birds’ social interactions and foraging behavior.